Pacific Nations Have Long Been Japan’s Largest Threat in Fukushima Release

- Jan 23, 2024

- 4 min read

Katherine Flint| South Pacific Fellow

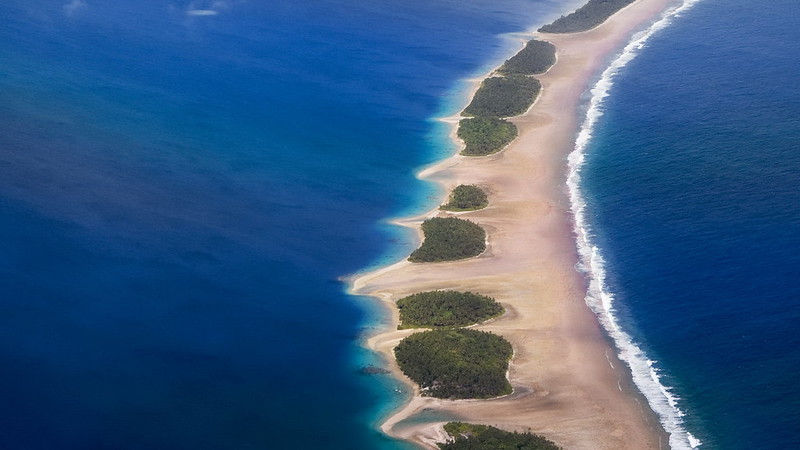

Image credit: Keith Polya via Flickr.

Pacific Islanders have long been custodians of the world’s oceans. For generations, they have fostered a deep connection with the vast blue expanse that surrounds their island homes, and embedded within the Pacific’s cultural fabric is a profound understanding of the delicate balance between humanity and the marine environment.

Therefore, when Japan commenced its discharge of radioactive wastewater from the Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear power plant into the Pacific Ocean on 24 August 2023, deep feelings of concern and dismay swept across Pacific communities. The decision resonated deeply with Pacific Islanders, stirring memories of the region’s own nuclear legacy, marked by over three hundred nuclear tests conducted on multiple island states between 1946 and 1996. The release also amplified worries about the potential environmental impact on the already fragile marine ecosystem they hold dear.

In the immediate aftermath of the discharge, protests surfaced across the Asia-Pacific, including in Suva, Fiji, which serves as the headquarters of the Pacific Islands Forum. Vanuatu urged Japan not to continue with the discharge ‘until and unless the water is incontrovertibly proven to be safe.’ The Solomon Islands stated at the UN that it was ‘appalled’ by Japan’s actions. Niue observed that the discharge would be ‘a transboundary and intergenerational issue’. The Pacific Islands Forum Panel of Scientific Experts noted that Japan had ‘chosen expediency over the health of the ocean, its ecosystems, and the people who depend on them.’ And Henry Puna, Pacific Islands Forum Secretary General, remarked ‘we must prevent action that will lead or mislead us towards another major nuclear contamination disaster at the hands of others.

In the midst of this passionate outcry, an intriguing oversight emerged: eerily similar events, now faded into the recesses of memory, unfolded between Pacific nations and Japan several decades ago.

In 1979, Japan announced plans to experimentally dump radioactive wastewater into the Pacific 900 kilometres southeast of Tokyo and 100 kilometres north of the nearest of the Mariana Islands. Strong opposition from Pacific nations followed: the Tenth Meeting of the Pacific Islands Forum strongly condemned Japan’s proposal; the Palau, Guam, Northern Marianas, and Federated States of Micronesia legislatures passed resolutions in protest; and Kiribati and Nauru successfully led an international movement to permanently engage a moratorium on ocean dumping of low-level radioactive waste. Seventy organisations with a total membership of more than 12 million people joined in a petition presented to the Japanese Diet (Parliament) in protest of the proposed plan. Ultimately, Japan never commenced dumping operations.

Four decades on, the Pacific has again been heard across oceans. However, the way in which Japan has pre-empted and responded to Pacific outcry this time around suggests a calculated and tactful plan is being crafted to address the backlash, perhaps driven by the experience of Pacific activism in 1979.

2023 saw Japan repeatedly strive to divide and conquer Pacific leaders, using development assistance as a political tool to green light the ocean discharge. Japan has been the region’s second largest donor since 2021 – the year Japan first announced its Fukushima discharge plan – and contributed USD $618.46 million in that year alone. Throughout 2022 and 2023, Japan’s Foreign Minister, Hayashi Yoshimasa, continued to emphasise development assistance in meetings with counterparts across the Cook Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Palau, and Papua New Guinea, among others. Since, each of these Pacific nations have made statements in support of Japan’s Fukushima discharge, ostensibly influenced by the prospect of continued economic collaboration.

At the heart of Japan’s strategy was not a desire for approval from individual island nations, but rather a necessity to fragment the otherwise unified Pacific Islands Forum – the region’s key negotiating bloc. The Forum was unable to reach strong consensus on the issue, owing to the starkly diverging positions of its member countries. While Pacific Foreign Ministers released a joint statement on the Fukushima discharge following its 2023 meeting, the proclamation was cast in weak language and lacked any explicit condemnation of Japan’s actions. Evidently, Japan never needed to convince all Pacific nations of the safety of its plan, but merely needed to persuade enough to stifle a coordinated response.

It is not too late for Pacific nations to change course on Fukushima. Just as Japan learnt from its mistakes in 1979, the Pacific too should reassess its current stance in light of its own previously overlooked leadership on this very issue.

There is little more disheartening than a policy pursued beyond good judgement for fear of appearing disorganised or weak. Antithetically, changing tune on Fukushima would signify strength from Pacific nations, not only on this issue, but in all future matters where the credibility of the Blue Pacific as a unified political bloc is at stake.

In the face of such critical decisions, the geopolitical landscape remains overwhelmingly favourable towards the Pacific. Almost all major world powers are poised to deliver significant development aid to a region growing in strategic importance. As such, the Pacific has more to gain in standing up to Japan than they stand to lose in reneging on a position linked to development deals. In fact, numerous developed countries could fill this void if Pacific nations were to go back on their word to Japan. Of particular importance in this regard are China and South Korea, who have also firmly opposed the Fukushima discharge.

A final lesson to be learned from history: persuading Japan to halt its 1979 release of wastewater did not happen overnight. Pacific states lobbied Japan from 1979 to 1985 before Tokyo’s plans to dump radioactive waste in the Pacific were abandoned. While the 2023 release is already underway, the Pacific still possesses a window of opportunity to influence Japan’s stance. And in the context of a three-decade long discharge plan, a setback of just one year will constitute merely a footnote in the pages of history.

Katherine is the South Pacific Fellow for Young Australians in International Affairs. She is a New Colombo Plan Scholar for Singapore and Fiji and fifth-year Law and International Relations student at the Australian National University.

This experience has not only imparted in Katherine a love for the Pacific region, but also immersed her in a unique perspective that has become an invaluable asset to her approach to international affairs.

Comments